As the Impacts Section details, development finance institutions’ (DFI) safeguards have not reliably protected the rights of workers at DFI-financed hotels, nor have they reliably mitigated the investment risks associated with labor issues. Assessing and planning for labour safeguard compliance requires extensive information, not only about the safeguards and the laws and regulations of the project jurisdiction, but also about the workers, their expectations, sectoral norms, and prevalent axes of discrimination in the locality. This information, however, is often inaccessible to DFIs, whose due diligence resources are spread across numerous sectors and geographies, and DFI clients, who are often new to the hotel business and the project jurisdiction. The result of this lack of information is underperformance in due diligence and compliance.

As the Performance Standards recognize, the solution to this quandary is stakeholder engagement, DFIs’ and clients’ most powerful tool for identifying and addressing E&S risks. Engagement with labor organizations in the local sector will provide both parties with access to crucial information, an understanding of community expectations, sectoral norms and challenges, and key sources of risk. Modeled on time-tested policy solutions from public project finance and global framework agreements, the Compliance Accountability Policy embeds that engagement in DFI project cycles. Engaging with trade unions and global union federations compensates for DFIs’ difficulty in assessing diverse projects in varied contexts and clients’ lack of experience in the locality, the sector, national labor law, and international labor standards.

The Challenge of Compliance:

Development banks face a major challenge in implementing their labor safeguards, as well as those relating to other environmental and social concerns. In due diligence, DFIs are charged with accurately assessing the likelihood that their projects will comply with safeguards across diverse geographies, in unfamiliar conditions, and in partnership with a broad array of clients pursuing business projects at various stages in their development.

For example, to achieve labor safeguard compliance in their hotel projects, under Performance Standard 2, for example, DFI clients must have access to a great deal of information and expertise related to national labor law and its regulations, which may bind them to collective and sectoral bargaining agreements and arbitral decisions. Furthermore, the client’s obligation to provide reasonable terms and conditions of employment requires knowledge of local wage and hour law and hotel sector norms and trends, and to meet their obligation to base job decisions on job-relevant facts, they must understand and anticipate axes of discrimination in the locality. Clients must know the workers well enough to effectively communicate with them regarding their rights on the job. Beyond that, clients’ understanding must be strong enough to not only achieve compliance within their own organizations, but also within the project-related operations of their contractors, who may have no contact with the supporting DFI, but are bound to comply with the DFIs’ safeguards on the project.

Neither DFIs nor their clients typically possess this sort of information and expertise. To effectively anticipate and address labor safeguard risks, they must collaborate with those who do.

Because banks and their project partners lack the expertise and input needed to properly address environmental and social (E&S) risks, their due diligence fails to identify clients who are unable, unwilling, or otherwise unlikely to comply. Those who implement projects, who are often new to the hotel sector and the project country, also have little understanding of the E&S challenges of their investment. This chain of under-informed parties results in business plans and contractual arrangements that impede compliance. Labor violations are only identified when problems arise, long after banks have approved and disbursed funds, and by that point, they lack the necessary leverage to influence clients’ behavior.

What the CAP Does:

On most DFI projects, the banks’ due diligence, evaluation of client compliance plans, and final vote on financing the project occur long before any stakeholders are engaged. For labor safeguards, the result is uninformed due diligence and planning, which can lead to noncompliance. The funding institution only realizes this after their decision has been made and the banks have disbursed funds, leaving them with limited ability to enforce safeguards. Following the tested policy models discussed in the Foundations Section, the CAP inserts social dialogue early in the DFI project process where it can have the greatest contribution to DFI due diligence and client compliance.

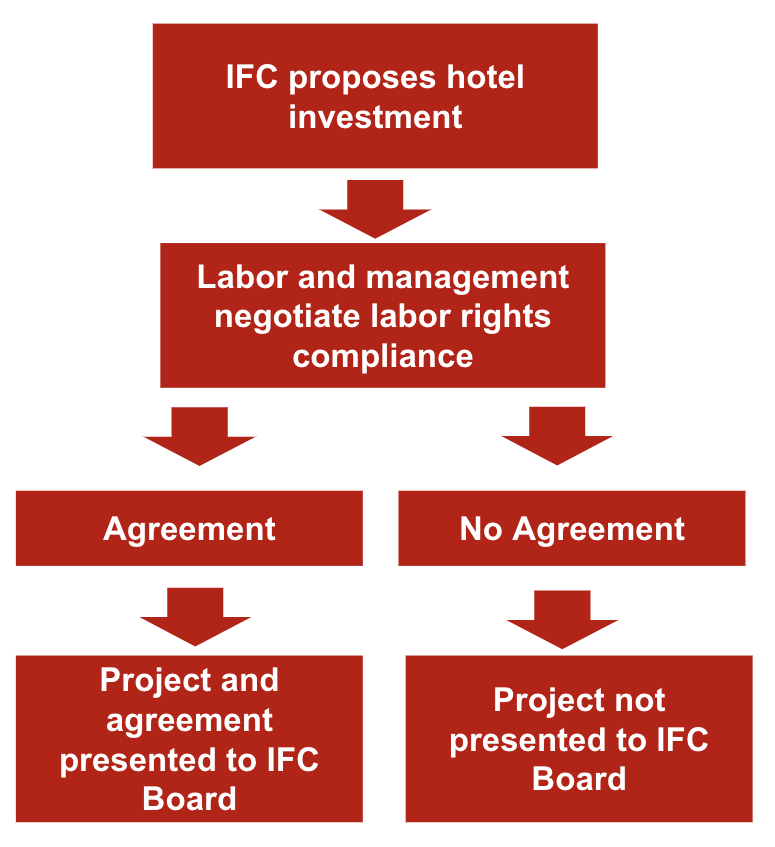

Under the CAP, as the DFI considering a project conducts its due diligence, they convene the team responsible for implementing the project and representatives from global union federations and trade unions representing workers in the local sector. Together, they discuss the relevant labor safeguard requirements and the team’s plan for meeting them. Only after the two groups come to an agreement detailing the project’s compliance plans would the project be reviewed by the DFI’s board.

The CAP requires no changes to bank safeguards and does not intrude on the traditional domain of collective bargaining. Since CAP agreements are intended solely to safeguard compliance, they leave the development of collective and sectoral bargaining agreements to national law.

Benefits of the CAP:

The CAP and the negotiations it requires fill the gaps in DFIs’ safeguard implementation. Rather than delaying stakeholder engagement until after the crucial decisions have been made, the CAP ensures that those decisions are made with the fullest appreciation of the labor safeguard issues facing the project. Clients unfamiliar with safeguards, the international labor laws they reflect, and their application in the project jurisdiction, sector, and workforce are paired with workers’ organizations experienced in all the above. Due diligence officers, whose broad geographic and topical responsibilities may limit their expertise in the locality and in labor rights matters, receive the support of local labor rights experts in evaluating projects and their compliance plans. Meanwhile, through the relationships the CAP negotiations establish, the client gains a knowledgeable partner as it pursues its compliance plans, and the banks’ due diligence officers gain an engaged partner in their project monitoring activities.